Floating vegetation island mats — living, drifting carpets of reeds, roots, peat and soil — are one of the world’s most surprising natural features. In several riverine and wetland regions, locals have learned to cross, farm on, and even build houses on these buoyant mats. Seasonal, fragile, and often ephemeral, floating vegetation islands are both ecological hotspots and unique strands of human resilience.

This guide explains what a floating vegetation island is, how these mats form and move, their cultural and economic importance, where to see them, and how travelers can experience them responsibly. We also include practical tips, high-quality image metadata you can use on your site, and an FAQ section that answers the most common questions about these living islands.

Table of contents

- What is a floating vegetation island?

- How floating vegetation islands form — the science explained

- Types of floating mats and their ecology

- Famous floating vegetation island regions (case studies)

- Loktak Lake, India (phumdis)

- Bangladesh floating gardens (dhap)

- Lake Titicaca and reed islands (Uros) — related phenomenon

- Lake Kyoga and Lake Victoria islands (Uganda)

- Cultural uses: walking, farming, and shelter on floating mats

- Seasonal behavior and why these islands “walk”

- Wildlife and biodiversity on floating mats

- Human impact: benefits and threats

- How locals maintain and use floating vegetation islands sustainably

- Best practices for visitors: safety, permits, and respectful travel

- Conservation and restoration efforts — science and community action

- Image guide (titles, alt text, captions, descriptions) for publishing

- Internal & external resources (DoFollow links)

- FAQs — quick factual answers

- Traveler Advise — why floating vegetation islands matter

1) What is a floating vegetation island?

A floating vegetation island is a mat-like aggregation of aquatic plants, roots, decomposed organic matter, and sometimes peat that becomes buoyant and detaches from the substrate. These mats can range from tiny patches a few meters across to large sheets spanning hectares. When large enough, people and livestock have been known to walk across them, build temporary platforms, or cultivate crops on them.

Key features:

- Comprised of live plants (reeds, sedges, water hyacinth, etc.) and organic debris

- Buoyancy comes from trapped gases in peat and interlocking root systems

- Seasonal — size and position vary with rains, floods, and droughts

- Ecologically rich — provide habitat, filtration, and carbon storage

This living biomass can move with winds and currents — thus the idea of “islands that walk.”

2) How floating vegetation islands form — the science explained

Floating mats originate through a few common ecological processes:

Vegetation expansion and matting. In productive wetlands, emergent plants like reeds and sedges spread laterally. Roots entangle and trap sediments. Over time the mat thickens.

Peat and organic build-up. Where decomposition is slow (cool or waterlogged conditions), organic matter accumulates and forms buoyant peat layers. Peat soaked with gases becomes light enough to float.

Hydrological change and detachment. Rising water levels, storms, or erosion can undercut a mat. Once buoyant, a mat can detach and drift.

Gas production. Microbial decomposition releases gases (like methane) that create lift within the mat.

From a physics standpoint a floating mat remains coherent as long as root networks and plant stems maintain structural integrity. When these are disrupted — by drought, wind, or human interference — the mat can break up.

3) Types of floating mats and their ecology

Floating vegetation islands are not uniform. Major types include:

- Hyacinth mats: Dominated by invasive water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). These may be dense and problematic for navigation but do form floating islands used by animals.

- Reed/peat mats (natural phumdis): Built from native sedges, reeds, and decomposed peat; often more stable and ecologically valuable.

- Constructed floating gardens: Deliberately made by humans, layered with organic material and planted (common in Bangladesh and parts of Asia).

- Rooted rhizome mats: Strongly interlocked rhizomes (e.g., certain marsh grasses) produce resilient mats that can support weight.

Ecologically, mats:

- Filter water by trapping sediments and nutrients

- Provide bird roosts and fish nurseries

- Act as carbon sinks (peat mats)

- Offer microhabitats for amphibians, insects and small mammals

4) Famous floating vegetation island regions (case studies)

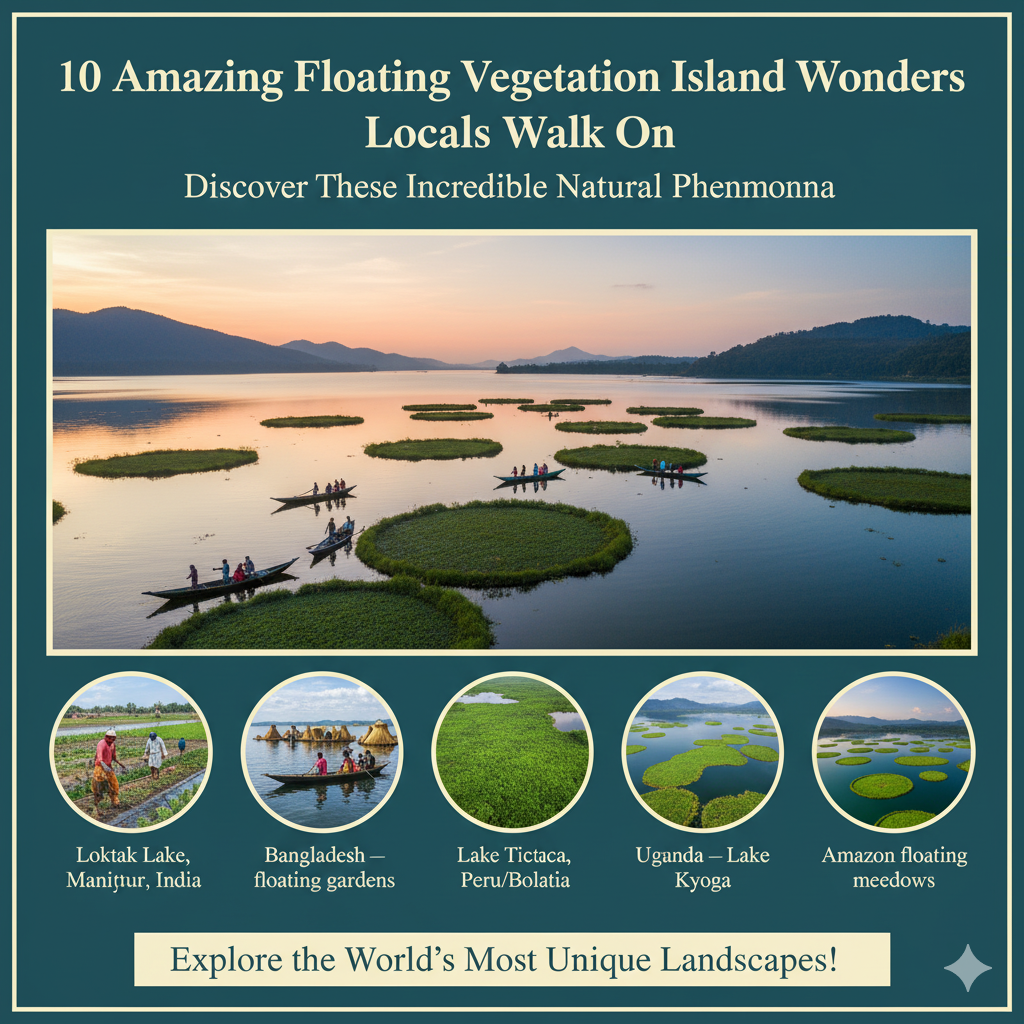

Loktak Lake, Manipur, India — the phumdis

Loktak Lake is home to the famous phumdis — large floating masses of vegetation and soil that can support homes and temporary structures. Villagers build stilted huts on or near phumdis, use them for fishing, and traverse them seasonally. The phumdis are culturally central and ecologically important, but they have also faced challenges from hydropower projects and changing water regimes.

Bangladesh — floating gardens and baira cultivation

In the flood-prone regions of Bangladesh, farmers create floating vegetable gardens using water hyacinth and other plant matter layered with soil. These baira or dhap gardens are deliberately constructed and maintained as an adaptive agricultural strategy during monsoon seasons.

Lake Titicaca & Uros reed islands (Peru/Bolivia) — a related tradition

The Uros people construct floating islands from totora reed; while technically different (they are human-made rafts rather than detaching vegetation mats), these islands highlight how cultures adapt to living on floating biomass.

Uganda — Lake Kyoga and Victoria floating mats

In parts of East Africa, floating mats appear seasonally and affect fishing routes. Villagers may cross mats or use them as temporary staging grounds for fishing activities.

South America — Amazon floating meadows

In the Amazon basin, seasonal floodplains produce vegetation mats that drift and create ephemeral islands used by wildlife and occasionally by people for foraging.

5) Cultural uses: walking, farming, and shelter on floating mats

Where mats are stable or managed, communities developed remarkable uses:

Walking routes. In shallow wetland landscapes, mats can link permanent ground to islands or boats, acting as natural causeways at certain times of year. Locals time their crossings carefully — these are the “walking islands.”

Floating agriculture. Farmers in Bangladesh and parts of India layer biomass and soil to create platforms for vegetables, especially during floods. Crops like spinach, eggplant and gourds are grown on floating beds.

Fishing and fish farming. Mats concentrate fish and provide shelter; fishers can anchor nets to mats or use them to process catch.

Temporary housing & cultural structures. On Loktak Lake, phumdis support temporary structures used in festivals or by small communities.

These practices show human ingenuity in adapting to dynamic wetland environments, making the floating vegetation island both a natural and cultural phenomenon.

6) Seasonal behavior and why these islands “walk”

The “walking” behavior is a function of seasonality. During wet seasons, rising water lifts mats and allows them to drift; winds and currents push them along. During dry seasons, mats may strand on shallows and become more stable.

Key seasonal drivers:

- Monsoon rains / snowmelt — cause detachment and mobility

- Storm events — can break or move mats rapidly

- Dry spells — mats may consolidate, dry, or deteriorate

Because the movement is often tied to weather cycles, mats can appear predictable to local knowledge but are inherently ephemeral.

7) Wildlife and biodiversity on floating mats

Floating mats are biodiversity hotspots:

- Birds: waterfowl and waders use mats for nesting and roosting.

- Fish: young fish shelter in submerged roots.

- Invertebrates: insects and mollusks colonize mats.

- Plants: specialized flora adapted to shifting substrates.

Mats can create microclimates: warmer or cooler pockets, nutrient-rich zones, and refuges during floods. This makes floating vegetation island habitats important for conservation.

8) Human impact: benefits and threats

Benefits:

- Provide livelihoods via fishing and floating agriculture

- Act as natural filters improving water quality

- Support unique cultural practices

Threats:

- Hydrological alteration: dams, water extraction, and channelization change water levels, destabilizing mats.

- Pollution: agricultural runoff and urban waste degrade mat health.

- Invasive species: invasive water hyacinth can overwhelm native mats and reduce biodiversity.

- Climate change: altered rainfall patterns and extreme weather threaten mat persistence.

Balancing human use with conservation is the challenge.

9) How locals maintain and use floating vegetation islands sustainably

Where communities depend on mats, traditional practices often include:

- Reinforcement: knotting mats, adding roots or woven materials to stabilize them

- Rotation: moving crops or grazing away to allow recovery

- Selective harvesting: taking only sustainable amounts of biomass

- Local governance: village rules about access and cutting

Successful cases show that community-led management, combined with scientific guidance, helps maintain mat health.

10) Best practices for visitors: safety, permits, and respectful travel

If you plan to visit a site with floating mats:

- Hire a local guide. They know safe crossing times and cultural norms.

- Check seasonal windows. Crossing is only safe at certain water levels.

- Wear sturdy, quick-dry footwear. Mats can be slippery.

- Don’t trample vegetation. Walk carefully and stay on established paths.

- Avoid burning or cutting mats. These actions degrade the ecosystem.

- Ask about permits. Some wetlands are protected or require permissions.

Ethical travel supports the communities that steward these unique landscapes.

Magic of Sandbars, Sandbars That Appear at Low Tide

11) Conservation and restoration efforts — science and community action

Conservation approaches include:

- Hydrological management — restoring natural flow regimes where feasible.

- Invasive species control — targeted removal and biological controls for hyacinth.

- Community-based monitoring — locals trained to record mat health and biodiversity.

- Research partnerships — universities studying carbon storage and habitat value of mats.

Successful restoration projects combine local knowledge with scientific monitoring and funding for alternative livelihoods to reduce destructive pressures.

UNESCO – Wetlands and cultural heritage

FAQs — quick answers about floating vegetation island mats

Q1: What is a floating vegetation island?

A: A floating vegetation island is a buoyant mat of plants, roots, and organic debris that detaches and drifts on water. These mats can support wildlife and, in some cases, human use.

Q2: Can people walk on floating vegetation islands?

A: In some regions, yes — stable mats or community-reinforced phumdis can be traversed. Always consult locals before attempting to walk on one.

Q3: Are floating vegetation islands natural or man-made?

A: Mostly natural, though humans sometimes construct or reinforce mats for agriculture or transport (e.g., Bangladesh floating gardens).

Q4: Are floating mats dangerous?

A: They can be unstable and slippery; risk arises from sudden water movement, weak root structure, and potential collapse. Use guidance and safety gear.

Q5: Do mats harm the environment?

A: Mats can be beneficial ecologically but may also harbor invasive species (e.g., water hyacinth). The impact depends on composition, scale, and human management.

Q6: How do floating vegetation islands affect fisheries?

A: They provide habitat for juvenile fish and structure for fishing, but heavy mats can also interfere with navigation and commercial fishing.

Q7: How are floating mats affected by climate change?

A: Changes in rainfall patterns, temperature, and extreme storms alter mat formation, mobility, and survival, threatening communities that depend on them.

Traveler Advise — why floating vegetation islands matter

A floating vegetation island is more than an ecological oddity — it is a living interface between land and water that supports biodiversity, local livelihoods, and a remarkable set of cultural practices. These walking islands tell a story of adaptation: how ecosystems respond to seasonal cycles and how people learn to live with change. Protecting these fragile mats and the communities that rely on them requires combining scientific research with traditional knowledge and community-led stewardship.

Whether you’re a curious traveler, a conservationist, or a student of human ingenuity, seeing a floating vegetation island is an invitation to rethink how dynamic and interconnected our wetlands truly are. Visit responsibly, support local stewardship, and help ensure these walking islands persist for generations to come.

Pingback: 7 Magical Singing Rivers Acoustic Canyons You’ll Love

Pingback: 10 Fascinating Facts About Geothermal Cooking Villages: Nature’s Hidden Kitchens