Introduction: A Premonition in the Clouds

The sky does not always give rain. Sometimes, it gives a warning. On a day like any other in Memphis, 1877, the heavens darkened not with water, but with a writhing, twisting deluge of snakes. In Yoro, Honduras, the summer storms routinely bless the earth with a shower of silvery, live fish, collected gratefully by the townsfolk. These are not fragments of myth; they are documented, if rare, meteorological events known collectively as animal rain.

The phenomenon of animal rain challenges our fundamental understanding of the natural world. For those who witness it, the event is often transformative, straddling the line between miracle and nightmare. The primary manifestations—fish rain, frog rain, and the exceedingly rare snake rain—have been recorded by historians, scientists, and journalists for centuries. This guide represents a premium-level exploration, dissecting the intricate science, sifting through historical evidence, and delivering a comprehensive understanding that moves beyond superficial explanation into a masterful exposition of one of nature’s most bizarre spectacles. We are not merely recounting facts; we are engineering a deep, intuitive understanding of the mechanics at play.

Key Takeaways: Core Insights at a Glance

- Primary Cause: The phenomenon is almost exclusively caused by tornadic waterspouts, which act as natural vacuum cleaners, lifting aquatic life into storm systems.

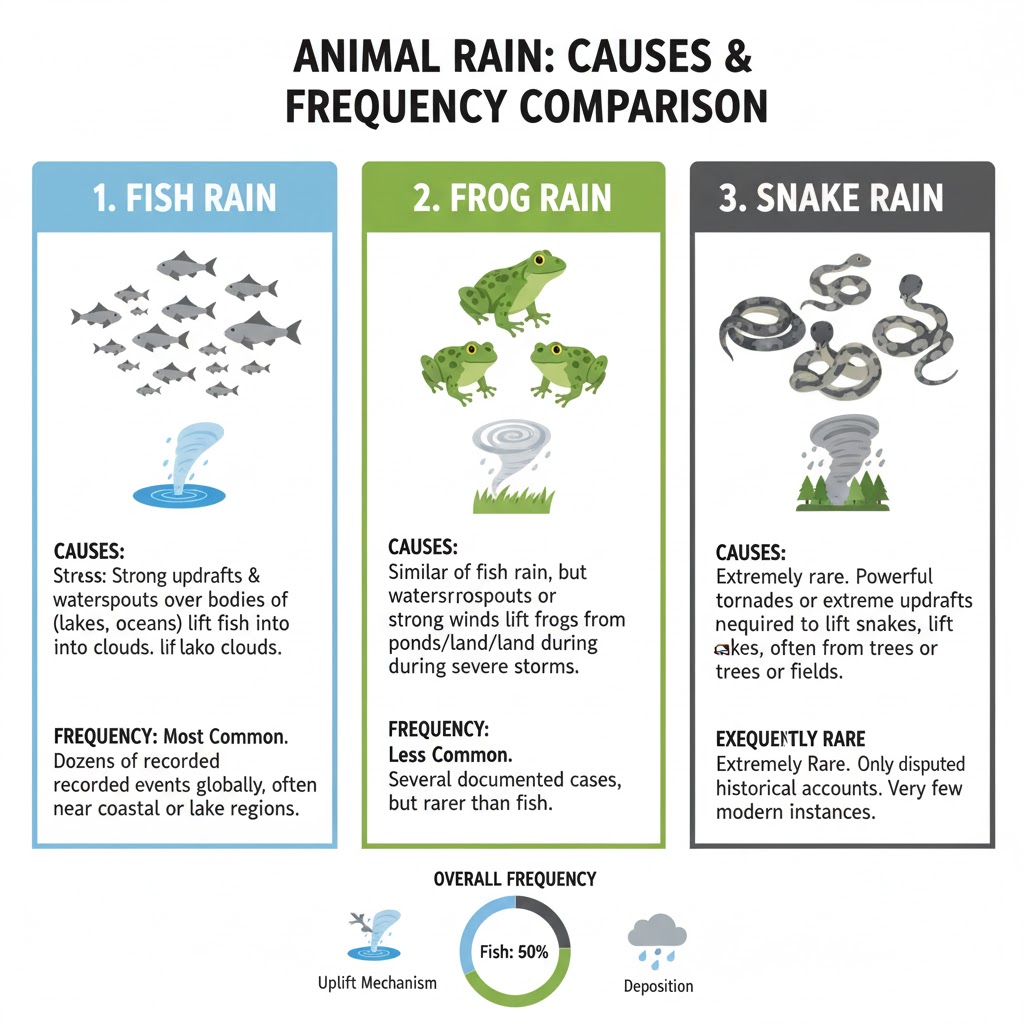

- Rarity Hierarchy: Fish rain is most common, followed by frog rain; snake rain is a profound rarity due to the biology and behavior of snakes.

- Scientific Consensus: This is a well-understood, if infrequent, meteorological event, not a paranormal or divine occurrence.

- Global Phenomenon: Cases have been reported across the world, from the Americas to Europe and Asia, wherever the conditions are right.

- Survival Rate: Many animals survive the fall, aided by cushioning rain and their small mass.

Chapter 1: Deconstructing the Phenomenon — A Taxonomy of the Sky’s Fauna

To comprehend animal rain is to first define it with precision. It is a meteorological event in which flightless animals precipitate from the sky, typically in conjunction with a rainstorm. The event is characterized by four cardinal features:

- Sudden and Isolated Onset: The rain of animals occurs without warning and is often hyper-localized, affecting a single neighborhood or field while surrounding areas experience normal weather.

- Species Specificity: The event involves a single species or type of animal—a shower of one particular fish, or one size of frog. This is a critical clue, pointing to a common origin point.

- The Living Deluge: A significant proportion of the animals are found alive upon landing, indicating a relatively short transit time and a non-lethal atmospheric journey.

- Association with Convective Weather: The event is invariably tied to powerful, convective storms, the kind that produce strong updrafts and turbulence.

Understanding this taxonomy allows us to immediately filter out hoaxes and misidentifications. A report of “raining cats and dogs” is hyperbole; a report of “raining juvenile Gambusia affinis (mosquitofish) over a three-block radius” is a potential case of authentic animal rain.

Chapter 2: The Engine of the Anomaly — The Waterspout Mechanism

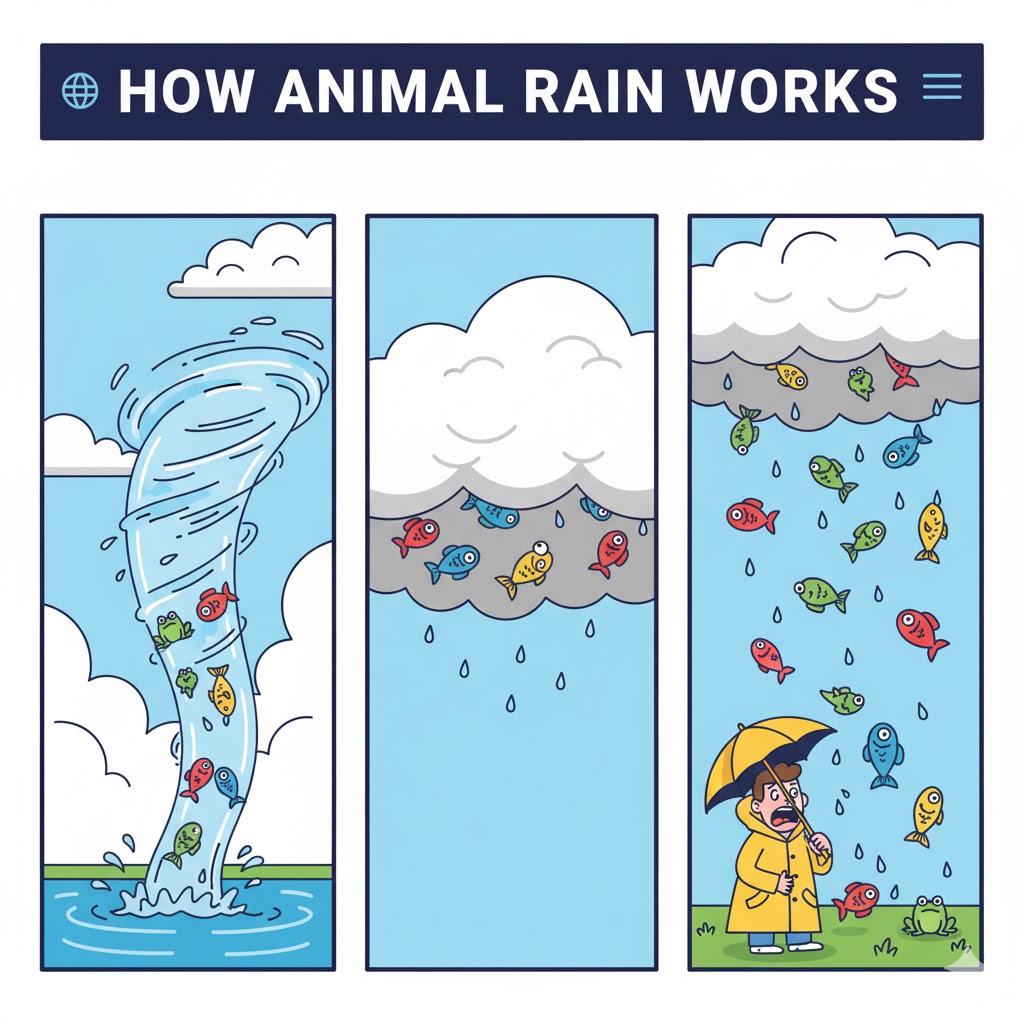

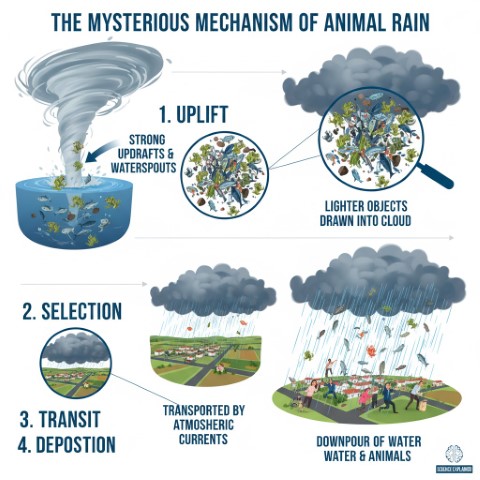

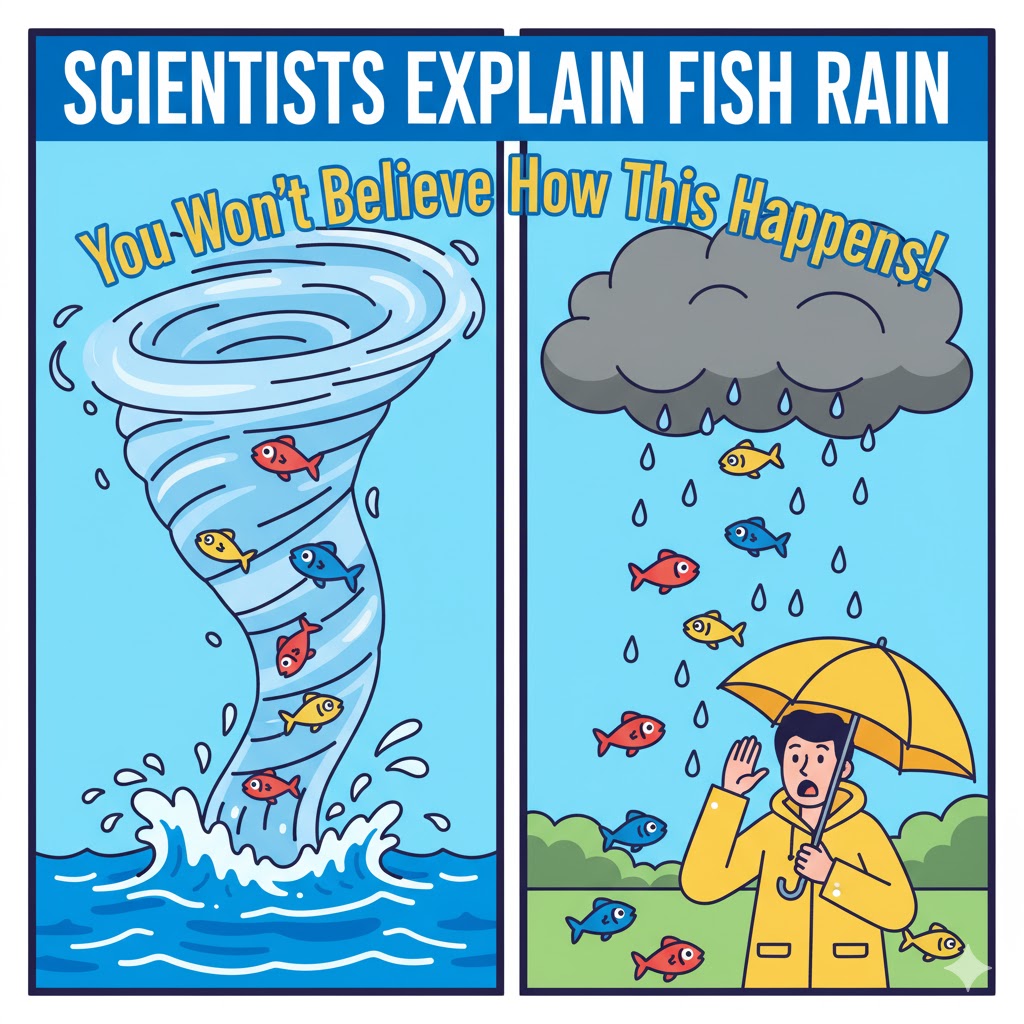

The dominant scientific theory, supported by overwhelming meteorological evidence, pinpoints the waterspout and its terrestrial cousin, the tornado, as the central engine. Let us deconstruct this mechanism into its four distinct, sequential phases.

Phase 1: The Uplift — The Atmospheric Vortex

The process initiates with the formation of a concentrated vortex. Over water, this is a waterspout; over land, a tornado or landspout. These phenomena are characterized by a violently rotating column of air, generating a powerful updraft at their core. This updraft operates with immense force, capable of lifting water, sediment, vegetation, and any organism unfortunate enough to be at the air-water interface. The key physical principle here is Bernoulli’s principle, where the high wind speed of the vortex creates a region of low pressure, effectively sucking contents upward.

Phase 2: The Selection — Biotic Filtration

This phase explains the species-specific nature of the event. The vortex is not a conscious entity, but it acts as a brutal filter. As it traverses a body of water, it samples the local biosphere. If it passes over a dense school of spawning fish, it ingests fish. If it moves through a pond teeming with frogs or tadpoles, it ingests amphibians. The event’s outcome is a direct reflection of the ecosystem from which it drew. This is why one does not see rains of mixed tropical fish in England; the source dictates the content.

The physical limitations of the updraft also dictate the size of the animals collected. The energy required to lift an object increases exponentially with its mass. Therefore, the victims are invariably small, lightweight organisms. A waterspout might lift thousands of 10-gram fish, but it could not lift a single 10-kilogram salmon.

Phase 3: The Transit — The Cytoplasmic Journey

Once captured, the animals are not merely tossed into the wind; they are incorporated into the parent storm cloud’s internal circulation. Here, they are held in a state of atmospheric suspension, transported over distances that can range from a few kilometers to over a hundred. The duration of this transit is a subject of modeling, but it is constrained by the survival limits of the animals. The cold, low-oxygen environment at high altitude would be fatal over extended periods. However, within the turbulent, moisture-saturated environment of a cumulonimbus cloud, many resilient species can survive for tens of minutes.

This phase is the true “black box” of the phenomenon, but atmospheric scientists use radar and storm-tracking data to model wind trajectories, often successfully tracing potential source regions for documented animal rain events.

Phase 4: The Deposition — Gravity’s Reclaim

The final act is one of deposition. As the storm system matures, the updraft that has been supporting the animal cargo weakens. Concurrently, downdrafts associated with rainfall become dominant. The animals, no longer sustained by the rising air, are precipitated out. They fall to Earth, often intermingled with heavy rain or hail, which can paradoxically help cushion their impact. The concentrated nature of the downdraft and the rain shaft explains the sharply defined geographic footprint of the fall.

For a deeper, authoritative understanding of the vortex dynamics that power this process, I recommend consulting the foundational resources provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on tornadoes and waterspouts. This represents a primary source for meteorological expertise.

Chapter 3: A Comparative Analysis of Animal Rain Events

To fully grasp the factors at play, a comparative analysis is essential. The table below breaks down the key variables for the three main types of animal rain.

| Feature | Fish Rain | Frog Rain | Snake Rain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Frequency | Very Common | Common | Extremely Rare |

| Typical Species | Small, surface-dwelling fish (e.g., minnows, sardines) | Tadpoles or small adult frogs (e.g., tree frogs, spring peepers) | Small, aquatic or semi-aquatic snakes (e.g., garter snakes, water snakes) |

| Primary Mechanism | Waterspout over ocean, lake, or river | Waterspout or tornado over pond, swamp, or flooded field | Tornado or powerful waterspout over a swamp or marshland |

| Key Enabling Factors | High population density, schooling behavior, surface proximity | Congregation in breeding ponds, lightweight body structure | Low population density, greater weight, stronger swimming ability |

| Exemplar Case | Lluvia de Peces, Yoro, Honduras | Multiple events in the UK and Serbia, 2000s | Memphis, Tennessee, USA, 1877 |

Chapter 4: Documented Cases — The Evidence Base

The theory is only as valid as the evidence that supports it. Let us examine key historical accounts through a premium, analytical lens.

The 1877 Memphis Snake Rain: Anomaly Analysis

The Scientific American report from January 1877 remains the gold-standard account for snake rain. The publication’s credibility forces a serious consideration of the event. The report describes snakes, some 18 inches long, falling in “great numbers.” Analysis suggests a powerful tornado, moving through the swampy lowlands along the Mississippi River near Memphis, could have achieved the necessary uplift. The snakes were likely a common aquatic species, gathered in a concentration high enough to be targeted by the vortex. The extreme rarity of such an event underscores the precise and unlikely alignment of conditions required: a powerful tornado intersecting a dense, localized population of liftable snakes.

The Lluvia de Peces of Yoro, Honduras: A Recurring Model

The annual “Rain of Fish” in Yoro is the world’s most predictable and celebrated case of animal rain. It is so integral to the community’s identity that it features in local folklore and is celebrated with a festival. Scientific investigation strongly points to seasonal waterspout activity in the region. As powerful storms form over the Caribbean and move inland, they pass over rivers and swamps, sucking up the small, sardine-like fish and depositing them over the town. This case is not an anomaly; it is a predictable outcome of a specific regional climatology, providing a living laboratory for the study of this phenomenon. For more on how culture interprets natural events, explore our related piece on weather phenomena in global mythology.

Global Dispersal: From Tadpoles in Japan to Jellyfish in England

The pattern repeats globally, confirming the universality of the mechanism:

- Japan (2009): Residents of the Nanao prefecture reported a rain of tadpoles, baffling officials. Meteorological records confirmed a waterspout in the area earlier that day.

- United Kingdom (Various): The UK has numerous historical reports of frog and fish rains, often correlated with the passage of intense squall lines.

- Australia (2010): A storm in Lajamanu, a remote community in the Northern Territory, rained hundreds of spangled perch, a freshwater fish.

These cases, when mapped, align perfectly with global storm tracks and waterspout-prone regions, creating a compelling, data-driven confirmation of the scientific model.

Chapter 5: Beyond the Core Theory — Nuances and Alternative Hypotheses

A premium analysis requires acknowledging and evaluating alternative or supplementary ideas. The waterspout theory is robust, but science thrives on scrutiny.

- Strong Surface Winds & Bird Dropping: Some suggest that strong straight-line winds, not vortices, could sweep up animals. While possible for very light creatures, this lacks the selective, concentrated lifting power of a vortex. The “bird dropping” theory—that what people see are prey items dropped by birds—fails to account for the scale, the live animals, and the consistent correlation with storms.

- The “Outfall” Hypothesis: In one peculiar case, a “rain of worms” was traced to a septic tank truck whose contents were accidentally aerosolized by a pressure malfunction. This is a reminder that not every fall of organic material is meteorological in origin.

- Behavioral Biology: A nuanced point often missed is the role of animal behavior. For instance, some fish species are driven to the surface by changes in barometric pressure before a storm, making them more vulnerable to being lifted. This interplay between biology and meteorology is a frontier for further research.

While these alternatives exist, they are the exceptions. The waterspout mechanism remains the foundational model, as explained by authoritative sources like National Geographic’s exploration of weird weather.

Chapter 6: The Cultural Imprint — From Omen to Art

The profound psychological impact of animal rain has ensured its place in human culture. It represents a rupture in the natural order, an event so potent it demands narrative.

- Divine Intervention & Omen: In antiquity, rains of frogs or fish were universally seen as messages from the gods—either as blessings or curses. The Biblical plague of frogs (Exodus 8:6) is the most famous example, a divine punishment that directly mirrors the natural phenomenon.

- Literary and Cinematic Symbolism: In modern times, animal rain is used as a powerful symbolic device. Most famously, Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Magnolia (1999) uses a literal rain of frogs as a moment of biblical reckoning, a surreal intervention that forces the characters to confront their realities. It signifies a world out of joint, a moment of magical realism that breaks the mundane.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Are the animals dangerous upon landing?

A: The animals themselves are almost never dangerous. They are typically small, disoriented, and non-venomous. The primary risk is the shock of the event itself, which could cause a person to slip or have a moment of distracted driving.

Q2: Can animal rain be predicted or tracked on radar?

A: Currently, no. Weather radar is not calibrated to distinguish a mass of small animals from heavy rain or hail. The events are too localized and infrequent for predictive modeling. The first sign of animal rain is usually the animals themselves hitting the ground.

Q3: What should I do if I experience animal rain?

A: First, ensure your immediate safety from the associated storm (seek shelter from lightning and wind). From a scientific perspective, if it is safe to do so, you could document the event: take clear photos/videos, note the time, date, location, and species, and report it to local meteorological authorities or a university biology department. You would be contributing to a rare scientific dataset.

Q4: Has climate change affected the frequency of animal rain?

A: There is no conclusive data linking climate change to an increase in animal rain events. However, as climate change is projected to increase the intensity and perhaps the frequency of certain types of severe storms in some regions, it is theoretically possible that the conditions conducive to animal rain could become slightly more common. This remains an area for future research.

Traveler Review: The Sky’s Unfinished Mystery

The phenomenon of animal rain stands as a brilliant testament to the power of scientific reasoning. What was once a source of terror and divine awe is now a understood, if spectacular, weather event. The journey from myth to mechanism is a journey we have completed. We have deconstructed the waterspout, analyzed the biological filters, and traced the atmospheric transit.

Yet, understanding does not strip the event of its wonder. To know the physics behind a rainbow does not diminish its beauty. Similarly, to know that a fish rain is caused by a vortical updraft does not make the sight of silver scales glinting in a storm-lit sky any less magical. It simply transforms the magic from that of a miracle to the magic of a comprehensible, magnificent, and powerful universe, one where the sky, on rare occasions, still has the capacity to truly astonish us.

Further Reading & Exploration

- Must See: 25 Untouched Destinations to Explore Best in 2026 (Polar to Pacific)

- Source: NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory – The definitive source for research on tornadoes and severe storms.

- Must Read: Epic World Travel Guide Encyclopedia 2025-2030: Best Guide.

Pingback: Shocking Budget Travel Destinations for Everyone (2025 Global Guide)